CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

The rise and fall of ‘King

of Portland saloonkeepers’

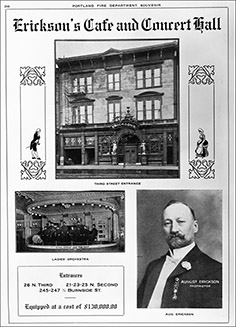

When the waters went down, Erickson found his building in dire need of repair. In this, he was in good company; but unlike pretty much every other Portland business, Erickson had made a killing during the month or so when the floodwaters filled the streets. So he was in a fine position to not only rebuild, but to bring Erickson’s Saloon back as something truly grand and special. The result, finished later that summer, was the bar that folks are thinking of when they mention Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson advertised it as having the longest bar in the world, at 684 feet — clearly they were measuring all the bars in the building to get that number, as city blocks are only 264 feet long. There was also an enormous pipe organ, a bandstand, and theatre stage for Vaudeville and concert performances. On the second floor, there were private card parlors and gambling chambers as well as more exclusive bars for wealthier patrons and a grill restaurant staffed with waiters in tuxedos. The third floor was divided into cubicles, which were where the girls worked — prostitutes and other sex workers, along with men and women who were cheating on their spouses and needed a quiet, discreet place for assignations. None of the sex workers were on the payroll, of course; that would have been considered unseemly. They were independent contractors, who rented their little sex dens from Erickson. The first floor was where Erickson’s famous “Dainty Lunch” was laid out. This consisted of a roasted quarter of a shorthorn steer, bread sliced an inch and a half thick, sausages, cheeses, pickled herring, sometimes lutefisk, and a variety of other delicious (and well salted) foods. The lunch was free, but no one had the crust to partake of it without buying at least one beer. It also had the advantage (to Erickson) of making sure all the patrons drank as much beer as they were able to handle, since they’d be pouring it down on full stomachs rather than empty ones. Erickson’s saloon was open to every race and nationality, and according to Stewart Holbrook’s recollections of the place, rowdy drinking songs in a dozen different languages competed with each other on a busy night. “Five minutes after the swift Telephone or the graceful Harvest Queen docked on the Willamette River, anywhere from 50 to 500 wage-slaves converged on Erickson’s like so many homing pigeons,” wrote Stewart Holbrook. “Seven minutes after arrival of a Northern Pacific or Southern Pacific train, in barged another crowd. It was said, and with some truth, that if you wanted to find a certain logger, you went to Erickson’s and waited; he would be there soon or late. It was common, too, to address letters to foot-loose friends in care of Erickson’s. The place often held hundreds of such missives waiting to be claimed.” The place had a significant economic impact on the town, too. It employed about 30 bartenders, plus of course there were also waiters, dancers, musicians, and cooks — not to mention the gamblers and hookers who paid Erickson for permission to operate on the premises. And bouncers: Erickson’s bouncers were famous. They were really good at being friendly and affable and non-threatening until you broke one of the house rules. Primarily those rules governed topics of conversation: No one was allowed to discuss politics, religion, or nationalist and racist theories; and any form of begging was forbidden. Once a man transgressed one of these rules, the nearest bouncer would transform as if by magic. A single verbal warning, very sharp and unmistakable, was usually given. After that, the remedy was expulsion from the bar, forcibly and not very gently, by one or more immaculately-groomed twinkle-toed gents who more than a little resembled the comic-book character Obelix.

|

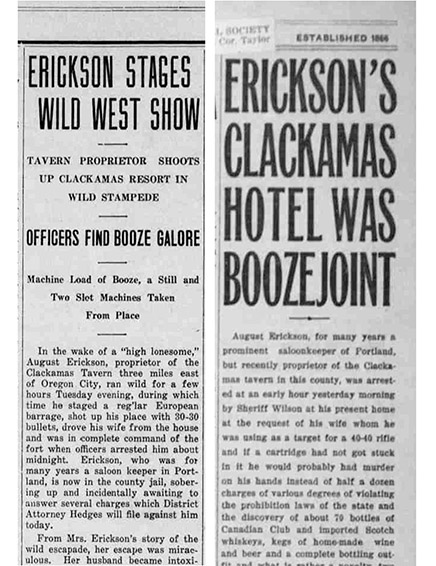

THE GLORY YEARS of Erickson’s lasted nearly two decades, until a fire broke out in 1913 and damaged the place severely; by the time it was repaired, Prohibition had kicked in. Even fairly early on, though, it was increasingly clear that Erickson was losing his battle with alcohol, and he started appearing with increasing regularity in the police blotter. In 1906 he sold half of the business to Fred Fritz; in 1915 he sold the rest, and moved to Oregon City to open the Clackamas Tavern. And, of course, we’ve talked about how THAT ended. In the end, Maria Erickson was awarded the tavern in the divorce. August Erickson drew a seven-month prison sentence, moved to Portland, and tried again, opening a malt shop with a secret blind pig — you paid for your drink at the soda counter, went around the corner, and waited by a hole in the wall for a hand to reach through with your booze. It didn’t last long. After they heard about it, the government sent a Prohibition agent over to the malt shop. He simply bought a drink, went to wait by the hole, and snapped a handcuff around the hand that reached through. Erickson was in prison serving time for this blind-pig operation when he died, in 1925. The Portland saloon that bore his name straggled on into the century, shrinking progressively smaller and smaller. In the early 2010s, the building started being redeveloped as low-income housing.

ERICKSON’S STORY WAS, as pop historian Bruce Haney puts it, “a real riches-to-rags story,” and quite the cautionary tale for any reasonably successful aspiring alcoholic. He did not die unlamented; thousands of railroad workers, loggers, and other working stiffs remembered him and his giant saloon very fondly. Stewart Holbrook was one of them — in his days as a logger and later a writer for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen union, he was a regular there. But as far as Portland’s ruling elites were concerned, it was good riddance. “At best, the place Erickson kept was a brothel,” sniffed The Oregonian in an obituary published after his death. “And at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

|