CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

Scenic gorge highway set the tone for Oregon roads

So, at Hill’s urging, they hired Lancaster as well as Olmstead’s son, John Olmstead, to design and create an elaborate network of scenic parks and boulevards to spruce up their city. It was a huge success, of course. The economic benefits that Seattle reaped were big, measurable, and — unlike Portland’s — lasting. Portland leaders could see what a big opportunity they’d missed. Then Washington hired Lancaster to design a system of access roads in Mount Rainier National Park, which are still legendary today — following Lancaster’s aesthetic goal of bringing visitors to beautiful scenery with roads and bridges that fit into and enhance that scenery. By this time Lancaster had a strong reputation as that rare creature, an engineer-artist — a Vogon poet, if you will. His projects made money, because they attracted people to see them. Meanwhile, Portland civic leaders and prominent citizens like Simon Benson and John Yeon were anxious to get even with Seattle with an even bigger, more spectacular road-and-parks project. So when railroad executive Samuel Hill and engineer Samuel Lancaster approached them to pitch a highway through the Columbia River Gorge that blended first-class engineering with magnificent, scenery-enhancing aesthetics, they got pretty excited.

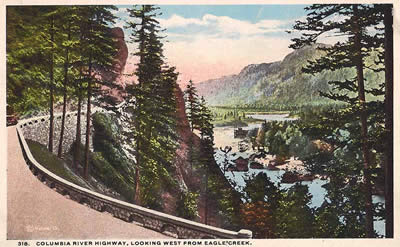

THEIR TIMING WAS excellent. In addition to Oregon’s desire to score on those pesky Seattle upstarts, the Columbia Gorge was a real problem that needed to be solved. It’s hard to think of this today, but in 1913, Portland and The Dalles might as well have been across an ocean from each other. Traffic between the Willamette Valley and the east was either on a railroad train or a steamboat. Passage wasn’t cheap and the journey wasn’t easy. Everyone could see that a highway would bring great economic benefits to the region. Everyone also knew the tourism potential of the Columbia River Gorge would be enormous. By now, most of Portland’s wealthy swells had outfitted themselves with automobiles, and the price of Henry Ford’s Model T had plummeted as he got his factory dialed in, to the point where most Oregon families could probably afford one. But Oregon’s dry summers and famously soggy winters meant that most roads would be pretty unpleasant to drive on most of the year. So, Hill hired Lancaster at his own expense to scout a route and draw up a plan. He scouted a route that threaded past waterfalls and scenic spots like the string in a pearl necklace — a “park to park highway,” as he put it several times. The road would be specially oriented to frame picturesque vistas, and it would harmonize with the scenery in such a way that Sunday driving motorists would find themselves immersed in the scenery — actually being part of the aesthetic effect, rather than just observing it. There would be long stretches of viaduct running right along the edge of the river, elegantly arched bridges spanning gullies and cliff faces, a spectacular windowed tunnel at Mitchell Point with views out over the water. Modern reinforced-concrete bridges would be faced with rocks carefully embedded to make the whole thing look like a rustic craftsman created it. Everywhere possible, drop-offs would be protected by a rustic stone-faced concrete guardrail, to stop cars from tumbling over the edge.

There was some resistance at first. One of the county commissioners dug his heels in, demanding that the project be narrower, uglier and cheaper, and pointing to some earlier surveying work that had been done. Luckily, he was outvoted.

|