CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

Pendleton Underground was like a secret mall

“Saloons with free lunches opened 24 hours a day and closed for one hour on Sundays for cleaning,” Crabtree writes. “Picture women hanging out of windows begging cowboys to come upstairs; and for a few bucks you could have a hot bath, a bed to sleep in, and company for a time. All this, and no hassle from the law.” It wasn’t until 1902 that the town council got around to passing an ordinance forbidding horse racing and cow roping on Main Street downtown. And even so, a number of the downtown saloons fought to keep things the way they were, fearing they’d lose business if cowboys couldn’t blow off steam in the street.

One of the sidewalk vaults under the Empire Block. On the left you can see the window opening for the basement room that adjoins it. The vault has had a concrete floor poured at a later date. (Image: F.J.D. John)As it happened, the cowboys picked a new spot, close by downtown, for their racing and roping sports. The spot they picked would, a few years later, become the Round-Up rodeo grounds. But that’s a story for another time. The upshot of all this rowdiness was that Pendleton was very much a “sundown town” back in the day. It was like an unwritten law that, especially on a Friday or Saturday night, nobody who wasn’t a young cowboy with a pistol on his hip and a bottle in his hand should ever risk being caught out on the streets of downtown after nightfall. (That’s an exaggeration, but not by much!) That was especially true for Pendleton’s “working girls,” who would be at serious risk of sexual assault, and members of the town’s rather sizeable Chinese community. Most likely, it was the Chinese who dug the tunnels connecting the sidewalk vaults together. Of all the Pendleton residents who used the underground to get around, they were the most industrious and probably also the most motivated to avoid contact with cowboys even during the daytime. Remember that scene that was in every other Yosemite Sam cartoon, where he gets his pistols out and tries to make Bugs Bunny “dance” by shooting at his feet? Warner Brothers did not make that up. That was a real thing that happened regularly when a liquored-up cowboy came across someone he was pretty sure he could get away with doing it to. And because of the prejudice of the day, basically any Chinese person was vulnerable to this kind of bullying at almost any time.

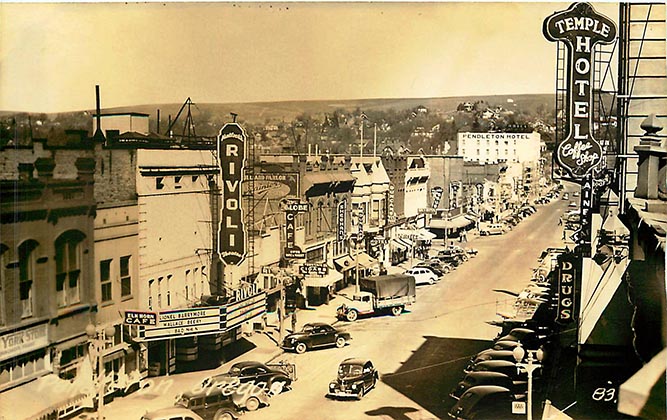

A postcard view of downtown Pendleton as it appeared circa 1940. At this time, most of the tunnels and vaults under the city streets were out of use, although the ladies working in the town’s bordellos probably still used them to get around discreetly. (Image: Postcard)If a Chinese fellow did press charges, the court would be very unlikely to convict unless there was straight-up murder involved. Even then, it was no sure thing. All the Chinese knew they needed to be off the streets at sundown.

Well, after Prohibition was enacted in Oregon in 1915, obviously anyone interested in moving liquor discreetly around the town. A fairly credible rumor has it that one tunnel actually led to a secret entrance at the city airport. Even before Prohibition broke out, they were in regular use by merchants who didn’t want to risk being robbed on the street; bordello girls and other working professionals at risk of being threatened and bullied; and, of course, the residents and merchants of Pendleton’s Chinatown.

|

The tunnel network was extensive, and varied widely in quality and hazardousness. They have been compared to an underground city; but probably a better comparison would be a giant sprawling shopping mall during a power outage. Folks from one building could pass under the street and patronize businesses on the other side. Some of them even had second storefronts in the basement to cater to the underground crowd. After Prohibition, those storefronts were pretty easy to convert into speakeasies. Pendleton had active, open bordellos going right up until the mid-1950s, most of them right downtown. When one of the girls needed something, especially late in the evening or at a time when she wasn’t dressed to go out, the tunnels were a great convenience. McCardy’s ice cream parlor’s “underground storefront” did a brisk business with the ladies of the evening, most of whom were big fans of ice cream sodas. They probably liked a little drinky from one of the saloons’ cowboy-free basement rooms from time to time as well.

The “underground storefront” in the basement of the Empire Meat Co., in the Empire Block. (Image: F.J.D. John)Visitors to and residents of Chinatown, both Chinese and otherwise, sometimes liked to indulge in a little opium smoking, and the underground was a great place to set up a secret opium den. In other words, the Pendleton Underground was a shadow community of folks who appreciated safety and discretion, and had a connection with one of the businesses whose basements allowed access. It’s amusing to contemplate a Friday night in Pendleton, with gunshots and thundering hooves and shouts and whoops ringing out above and a busy community of shopkeepers and working girls bustling back and forth in safety beneath the streets. Amusing, but maybe a bit misleading. Not all the businesses under there were benevolent and fun. Especially when it came to the labor contractors specializing in Chinese workers, who — according to Crabtree — used some of the more fortified basement rooms (with bars on the windows) to imprison workers who’d signed indentured-servitude contracts with their organizations. Today, a number of these tunnels have been reopened and cleaned up by a public-history organization called Pendleton Underground Tours. If you haven’t taken the tour, it’s very good, and the tour leaders do a really good job of balancing the history and folkloric aspects of Pendleton’s “underground shopping mall.”

|