CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

Minister’s ‘drunk tweets’ led to historical fistfight

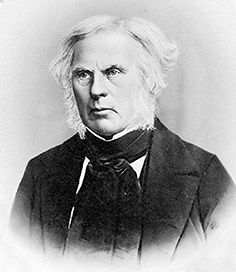

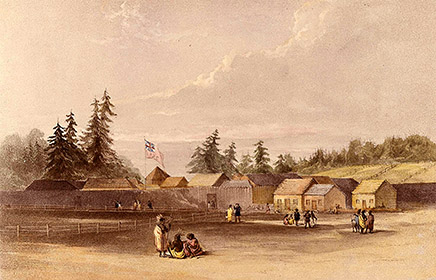

Even with a stick, Beaver was no match for McLoughlin, who was 6 feet 4 inches tall and built like a draft horse. After taking several kicks and punches, Beaver dropped his stick, which his wife picked up. McLoughlin wrenched the stick away from her and gave her husband a couple lusty wacks across the shoulders with it. Then several bystanders arrived to help Mary Beaver stop the fight.

“This Beaver spurned, and it is clear that he felt McLoughlin’s violence had delivered him — and perhaps the Company — into his hands,” writes historian W. Kaye Lamb. “Ill-concealed exultation as well as righteous indignation blazes up in the account of the affair that he sent to London.” Perhaps luckily for all involved, McLoughlin left two days later for a previously scheduled overland journey into Canada, and in his absence James Douglas was left in charge. Douglas was at pains to keep Beaver as happy as he could, and for some time he thought it was working. It should have been a great relationship, really, as Douglas and his now-wife, Amelia Connolly, had been the first marriage ceremony Beaver had presided over at the fort (Douglas and Connolly had, of course, been fur-trade-style spouses before that). But, it was not to be. The break literally happened in the middle of a letter Douglas was writing to London in which he copiously praises Beaver’s efforts in one paragraph, and a few lines later speaks very disparagingly and contemptuously of him. So what happened? Well, once again, Beaver sent a “tweet” in his report to London (which at this point he obviously well knew the head of the fort would be reading) that included this line: “I see the principal house in your Establishment made a common receptacle for every Mistress of an Officer in the service, who may take a fancy to visit the fort.” Douglas, incensed, dashed off a note to Beaver demanding that he explain what this meant, and who these “mistresses” were. This Beaver replied to in very formal terms, declining to provide any explanation, and after that, the two of them were no longer on speaking terms. So Douglas dashed off a lengthy letter to London rebutting Beaver’s accusations (and disclosing his consumption rate of brandy, port, and other liquors, as mentioned above), and at his very next opportunity Beaver embarked for London “for the purpose of instituting legal proceedings against Chief Factor McLoughlin,” as he put it. This he attempted to do after arriving home in May 1839; but nothing came of it, and shortly thereafter he was told that his services would no longer be needed, and was hit in the backside with a check for 110 pounds sterling to settle his claims against McLoughlin and the Company.

|

McLoughlin wouldn’t get off unscathed either; the Hudson’s Bay Company brass in London never quite trusted him after this incident, especially as he started befriending American settlers who arrived in the country destitute. Eventually they tried to “kick him upstairs” by offering him a promotion that would require him to move back east, and he resigned and took up a land claim at Willamette Falls in what is now Oregon City.

But there are a couple things that should be mentioned about him, and maybe they actually make up for all the unnecessary trouble and drama he caused: First, there’s the issue of slavery. The Indians of the Pacific Northwest practiced slavery, pressing war captives into forced service, and under McLoughlin the Hudson’s Bay Company followed this custom, a blatant violation of English law and Company policy. Beaver, when he learned this, had a fit, and it’s chiefly thanks to him that this practice was stopped. He also had a point about “fur-trade marriages.” The problem with them was, the women were committed to them, but the men often were not. Even Marguerite McKay was a former cast-aside fur-trade wife; she’d been “fur-trade married” to trader Alexander McKay, who had deserted her. This happened a lot in the Company’s remotest outposts, and resulted in a lot of abandoned wives and semi-orphaned children dependent on the charity of the Company. It was blatantly unfair, clearly immoral by the lights of the church, and Beaver did his best to stand up to it. In spite of all the trouble Beaver encountered, including the healthy portion he laid upon himself, Beaver did some real good at the fort — giving at least a dozen “fur-trade wives” some stability and legal status, and ending slavery in the Oregon Territory for good. It makes one wonder how much different history would have been, if only Beaver had had a little less of a tendency to drunk-tweet, and a little more generosity of spirit.

|