CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

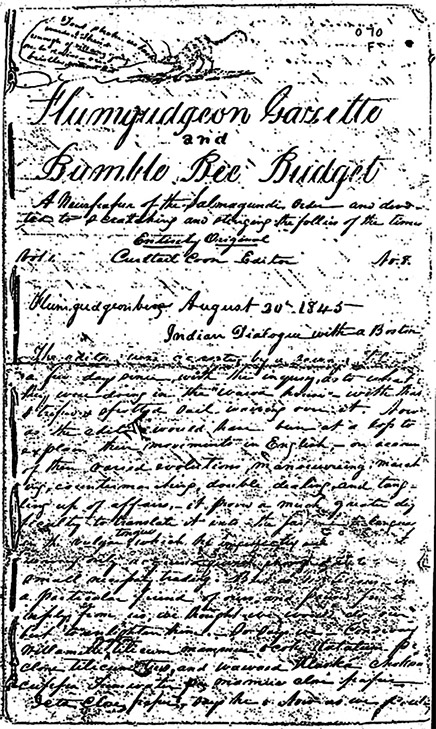

Oregon’s first newspaper was written out longhand

Powell had been working on a biography of a bellicose, colorful transplanted Southerner, a Virginian named Charles Edward Pickett, who moved from Oregon City to Sacramento near the end of the Mexican War and hit the political stage there like a wrecking ball. While researching Pickett’s contributions to a California newspaper, Powell came across a letter to the editor in which Pickett spills the tea: The Coon had been Pickett himself. Pickett’s nickname was “Philosopher Pickett,” which makes him sound like a harmless enough guy. This was emphatically not the case, though, particularly when he was young. And yes, he was related to George Pickett, the Confederate general famous for Pickett’s Charge; the two were cousins. The whole clan was known, back home in Virginia, as “The Fighting Picketts.” Philosopher Pickett was a prickly, aristocratic Virginian of the type that usually adopted “Colonel” as a nickname later in life, and maybe he would have done so if he hadn’t already had one. He left Virginia in 1842 when he was 22 years old, lured by the opportunity to “win” the Oregon country away from Perfidious Albion. He ended up joining one of the earliest wagon trains to Oregon, in company with Peter Burnett and Jesse Applegate. Upon arriving, he found that the Methodist missionaries had staked enormous claims to the best portions of the Willamette Valley. This offended his sense of fairness, so he waded into the fray, staking his 640-acre claim in the middle of the Methodists’ reserve, at the confluence of the Clackamas and Willamette rivers in what is now Gladstone. “The church was unsuccessful in ousting him,” Powell reports, “even though it went so far as to incite the Indians to attempt to murder him. The monopoly was broken, and the land-hungry settlers poured in after him.” Pickett also feuded with the territory’s Indian agent, Dr. Elijah White, and actually managed to get White fired from his job. The gig was then offered to him, but by the time the offer came through he’d moved to California. As for the “Philosopher” part of his name, well, Pickett was one of the founders of the Pioneer Lyceum and Literary Club, and served as its secretary. The Lyceum was the organization that launched The Oregon Spectator in 1846, and Pickett had hoped to be tapped as the paper’s editor. In fact, his decision to publish The Gudge may have been intended to demonstrate his suitability for the editor’s chair; when Pickett launched The Gudge, the printing press that the Lyceum had purchased to print the Spectator was already on its way “around the horn.” If that’s the case, it didn’t work. The Methodists, who were furious with him for breaking up their giant land claim, pulled some strings and got him taken off the short list, and the job went to William G. T’Vault instead.

|

This snub may have been what prompted Pickett to leave Oregon. He was in the first issue of the Spectator with Oregon’s first real-estate ad, for townsite lots in what is now Gladstone — he’d carved up his claim and was selling it off. A few months later, he quit the territory and moved to Sacramento. In California, Pickett got into a fight over a property line that culminated in him blasting his neighbor with a shotgun as the neighbor charged him with a pickaxe. He was prosecuted for murder, but found innocent. The following year he was elected as a delegate to the first California constitutional convention. Later attempts to get elected to public office in California did not pan out for Pickett, so he continued publishing his ante-bellum Jacksonian populist screeds and working his land there. He may have wished he’d stuck around Oregon with its “flumgudgeon theater,” as apparently he found California’s legislature to be even worse.

The letterpress used to print Oregon's first printed newspaper, the Oregon Spectator, is on display at the University of Oregon's Allen Hall, home of the School of Journalism and Communication there. This press was actually shipped "around the horn" to Oregon in 1846 — almost a year after Edward Pickett created Oregon's first newspaper, writing every copy out longhand. (Image: Curt M. Thomas)During the Cayuse War that followed the Whitman massacre, Pickett returned to Oregon to try and lend a hand in rounding up a militia company to attack the tribe. He also lent his pen to a series of unsuccessful but colorful attempts a decade later to keep Oregon slavery-friendly and to block the rise of Edward Baker as Oregon’s senator. But his life was in California now, and for the most part he stayed there. Shortly after the Civil War Pickett had one more brush with fame when, during a trial before the California State Supreme Court, he assaulted one of the judges, seizing him and dragging him off the bench for an epic pounding. A pounding did indeed ensue, but it wasn’t the judge who took the brunt of it; and it was followed by a sensational contempt-of-court trial that resulted in Pickett spending eight months in jail. He later sued the court for $100,000 for this affront, but lost. Pickett died fairly young, at the age of 62, in Mariposa in 1882. Like poor James Marshall, the ex-Oregon farmer who touched off the California Gold Rush, Pickett really should have stayed in Oregon. On the other hand, given his pugnacious support for the Confederacy in general and slavery in particular, it’s probably just as well that he did not.

|