CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

Did this tiny, scary road save Oregon beaches?

There was a difference, though. Landowners on the coast weren’t stealing anything — they had legitimate legal land claims on beachfront property. Legally there was nothing (yet) to stop them from blocking public access, and thereby cutting off any neighbors who used the beach to reach the outside world, except for a waterfront version of “range custom” — except in Clatsop County, where it was now the law of the land.

Nearly everyone in the state was all in favor of good roads. By 1912, most Oregonians were also all too aware of the benefits that had come from Samuel Lancaster’s work up in Washington following Seattle’s Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition three years earlier. In the early 1910s, when it came to good roads, it really was true that “if you build it they will come.” And everyone knew it. For Oregon to grow its economy into the 20th century, it would need a good solid network of roads suitable for use by driven-wheel vehicles (bicycles, cars, etc.; things that required traction to go) as well as horse-drawn ones. So Oswald West brought these two constituencies together in his proposal to extend Clatsop County’s road law all the way south to California. “I pointed out that thus we would come into miles and miles of highway without cost to the taxpayer,” he recalled, in a 1949 interview. “The Legislature and the public took the bait — hook, line, and sinker.”

Speaking for myself, I doubt it. A canny politican, West could see that he would have two main sources of resistance to his plan: Landowners to the south, and libertarian-leaning plutocrats who felt that government should meddle as little as possible in other people’s property interests.

|

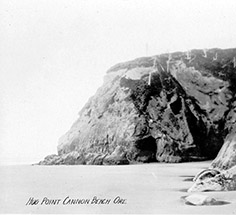

As West well knew, he could do nothing to counter resistance from landowners with beachfront property to the south. But in 1912, partly because it was so hard to reach those places, there just weren’t very many of them. Other than settlements at the mouths of major rivers and bays, like Tillamook and Newport and Marshfield, the Oregon coast was almost a wilderness area. As for the libertarian plutocrats, well ... most of those, living in the Portland and Salem areas, had at least once vacationed in Clatsop County and benefitted personally from having a legal right to access the beaches there. And at Hug Point, the hand-cut roadbed became Exhibit A in the case for beach-as-highway. Would the anonymous benefactor have invested the time and dynamite to make that road if he hadn’t had the protection of the law? Of course not. So when West came before the Legislature to make the case that the state should claim a right of passage all along the beach, defined as the strip of wet sand between the low and the high tide marks — he got very little resistance indeed. To be sure, the landowners with beachfront property were mostly defiant. But, as noted, there just weren’t very many of them, and that actually had a lot to do with the problem the beach-highway scheme would directly address: there was no way to access their property. The law was passed, duly signed into law in 1913 ... and the rest is history. But the whole debate might have gone down in flames if it had not been for Clatsop County — and the anonymous benefactor who blasted that road into the side of Hug Point.

|