CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

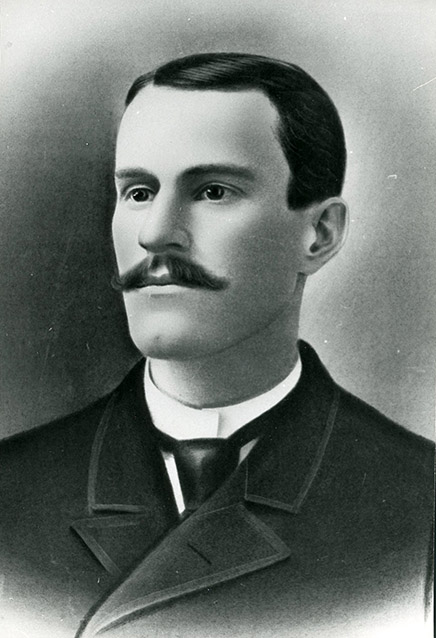

Frederic Balch evoked spirit of old, wild Oregon

No village, Gertrude said, was too remote for him to take the time to journey there, if “at the end of the trail he found a representative of some old tribe, who remembered ... legends told by his forefathers.” Also, Frederic’s respect and reverence for the Indian cultures was very unusual for his time, and his friend and fellow Congregationalist George Himes confirms this. This sympathy for the Indians and reverence for their traditions actually may have caused some hard feelings among the neighbors. A case in point might be Frederic’s childhood crush, Genevra Whitcomb, a neighbor’s daughter in Lyle. Frederic proposed to Genevra, and she turned him down but they decided to remain friends. After that, he seems to have been well on his way to getting over it, but then she got pneumonia and died; and he, as the only lay preacher in town, was more or less forced to officiate at her funeral. Gertrude said the funeral traumatized him badly, and blighted all his prospects of future happiness. His natural sadness at the death of a friend was transformed into something much more intense by the sight of her pale, cold face. “(He) was absolutely sincere when he said he no longer loved Genevra and she meant no more to him than any other of his friends,” Gertrude wrote, in a letter in 1949. “I am positive if he had not been compelled, as it were, to officiate at her funeral, and to look upon her dead face, that the remainder of his life would have been a far different story and a much happier one.” Genevra’s family, interviewed years later after Frederic was famous (and long since dead), spoke about him with a strange bitterness. Interviewed by biographer Wiley in 1945, Genevra’s sister Elizabeth said he was lazy and a lousy preacher, adding that the whole Balch family was “mentally affected.” “The world would be better off without people like that,” she added, to Wiley’s apparent astonishment; it’s certainly in questionable taste to say such things about the dead, and Wiley noted that “No other person of the many I interviewed made any disparaging comments about the Balches.”

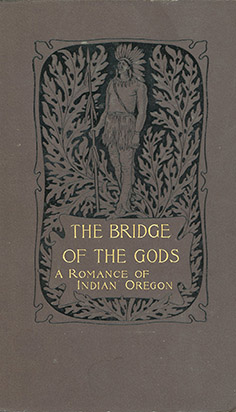

The book sort of opened up a new genre of romantic fiction around the intersection of Indian culture, frontier European-American culture, and the spiritual aspects of the magnificent scenery and sublime forces drenching the Columbia River Gorge. In a real sense, it set the tone of what home looked and felt like for new generation of Oregonians.

|

After his death in 1891, some of Balch’s other works got published, including a novel titled Genevieve: A Tale of Oregon and a short story, “How a Camas Prairie Girl Saw the World.” “Although he did not live to see his 30th birthday, Frederic Balch was a major regional writer who contributed significantly to Oregon’s sense of itself,” historian Stephen Harris writes. He also was the first Northwest writer to take Indians and their legends seriously and cast Indians as major characters in a novel.

He was a sensitive, gifted writer placed in a region of sublime natural beauty that would have drenched him in spiritual food, and yet there was bread that had to be earned and chores that had to be done, and no way to access the kind of culture that Eastern writers like Hawthorne and Poe (or even Southern authors like Mark Twain) could take for granted. It was a bit like being chained to an oar in a Roman galley gliding majestically past the Amalfi Coast, unable to fully appreciate or enjoy the intellectual opportunities of the setting. “The splendid wilderness that inspires the creative impulse also inhibits its fulfillment,” Harris writes. “Cultural isolation, poverty, hard physical labor, and a dearth of educational opportunities made the 19th-century frontier a harsh and unforgiving environment, to which the Muse was typically a stranger.” Frederic Balch was able to overcome these headwinds by, basically, working himself to death to make of himself a rare exception to that iron rule. In doing so, he gave us an emotional snapshot of Oregon as it was in the age when everyone spoke Chinuk and the rivers flowed wild and free swarming with salmon. He deserves a better fate from history than to be remembered as a guy with the same surname as a drunk shotgun-wielding Portland murderer.

|