CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

State’s land grab nearly ended in disaster for them

Over beers at the Wolf Creek Tavern, the Stumbo brothers hatched a wild and audacious scheme for how to meet the challenge. And after getting some probably much-needed legal advice from Corinne, they got started on it right away. To preserve their rights to their property, they had to make a clear assertion of their ownership before the ten years ended. According to the statute, the clock could be stopped “by the owner’s entry upon the land, when accompanied with an explicit declaration of his purpose to repossess himself thereof, or by such an open and notorious act of dominion as to make that purpose manifest.” So the Stumbos prepared a “notorious act of dominion.” They built and painted a set of very neat barricades and, at a not-too-busy time on a not-too-busy day (Sunday, August 12) they erected them on each side of the Stumbo Strip, in the middle of Highway 99. “PRIVATE PROPERTY,” the signs on the barricades read. “Permission to pass over revocable at any time.” They blocked the highway for 30 minutes. As hundreds of cars piled up behind their barricade, they walked from car to car handing out handbills that explained what they were doing and why. “We have decided to remind the state of our ownership,” the handbills read, in part. “In order to repossess our land it has been necessary to temporarily close the highway.” There were, of course, some representatives of the Fourth Estate on hand with cameras and notebooks to capture the whole thing for the next day’s newspapers and radio broadcasts. Word spread very quickly after the reporters started calling officials for comment. The Oregon State Police dispatched a riot squad to the scene from Grants Pass with orders to reopen the road by force; but, luckily for all involved, the Stumbos had reopened the road long before they could get there, having made their point. Then, first thing the following morning, Corinne filed an application with Douglas County to operate the strip as a toll road.

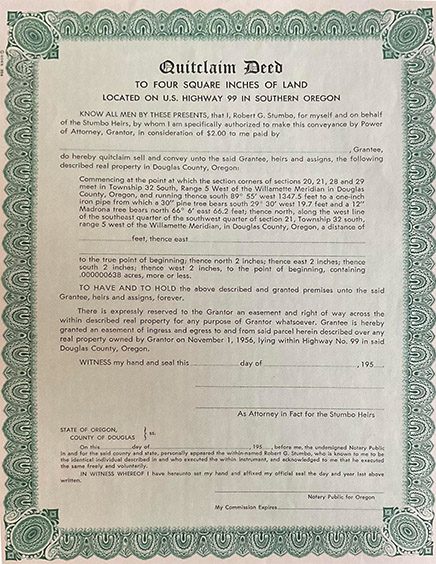

In 1957, $100 was worth about $1,150 in modern money. Even for a tiny strip of unbuildable land, it was an insultingly low sum. So rather than engage, the Stumbos listed the strip for sale with local real estate broker Leslie Kellow. As a toll road, of course, it would be worth a lot more than $100; so, just to twist the Highway Department’s tail a little more, they set the price at $250,274. Just in case anyone might think they were serious, they advertised it as having “Highway frontage on two sides!” and being located “At the end of the longest dead-end street in the West!” The state responded by threatening to just condemn the strip outright. So, just to make that a little harder for them to do, the Stumbos platted a subdivision on the strip. They literally carved it up into thousands and thousands of tiny squares, two inches on each side, and started selling the little nuggets of asphalt for $2 each. Buyers received title to their four-square-inch property with distinctive, suitable-for-framing quitclaim deeds specifying the location of their little piece of highway paradise. Of the $2 price, $1.50 went for filing fees at the county, and the other 50 cents was being given to charity. The goal, of course, was, now that the Highway Department was preparing to simply gobble up the Stumbo land, to make it as hard as possible to digest, by making the state file hundreds of condemnation suits rather than just one. This really quite brilliant move had a couple of unintended consequences, though. First, it got the Stumbos on the wrong side of Douglas County, officials of which really did not want to have to deal with all the extra work this was making for them. In what can only be explained as an institutional temper tantrum, the county arrested Bob Stumbo and threw him in the county jail for the night, charging him with selling subdivision land before the plat was filed. They actually threatened him with a $5 million fine, adding up the maximum penalty for every single parcel in the plat whether it was sold or not. Bob was back out of jail the next day, of course, and the charge was dismissed soon thereafter.

|

The state, when it saw that, pounced. In court they argued that they should be able to condemn all the tiny properties in one condemnation hearing, rather than having to litigate each one, because all the properties had a common interest that would be extinguished if the state condemned them one by one. You can’t sue one person to extinguish an easement right owned by someone else — you have to sue both of them at the same time. The judge agreed, and with that, the Stumbos were out of luck. One hearing would decide the fate of all the tiny properties. They also were out of luck on their $250,274 valuation of the property as a potential toll road, as the court ruled the condemnation value should be set at the land’s value when the trespass first occurred, back in 1949, rather than its value at the time the condemnation was filed. So the Stumbos were awarded a measly $125, plus interest. Bob was especially disappointed in this outcome because, if he’d thought of the easement issue early enough, it could have been used to essentially make the whole strip immune from condemnation. There are, or at least there were at the time, certain types of property that are not subject to condemnation, including cemeteries and churches. “If we’d given one plot to a church, the land never could have been condemned,” Bob said ruefully afterward. But what was done was done, and there was nothing that could be done now other than appeal the verdict — which the Stumbos duly did, twice. Eventually it reached the state Supreme Court, which, as expected, upheld the verdict — and the Stumbos were done. “My father believed Ken Kesey’s book Sometimes a Great Notion was loosely based on the road closure incident,” said Bob and Corinne’s youngest daughter, Stacy. “The fact that main characters were ‘Stampers’ may be just coincidence.” It may be. And, of course, the Stampers were a family-owned “gyppo outfit” too, and their motto, “Never Give an Inch,” wouldn’t be entirely out of place on the Stumbo family crest. The timing lines up; Kesey was living in Springfield at the time of the Stumbo Standoff, and had just graduated the month before from the University of Oregon. He definitely knew about this story.

In Oregon, though — particularly southern and eastern Oregon — the event really struck a chord with a population increasingly weary of bureaucratic overreach. And decades after the incident, the name “Stumbo” still commands respect among those who remember the events. “Many years later when I interned for (Sen. Bob) Packwood I met with Mark Hatfield, who celebrated the Stumbos’ ingenuity and dedication to fighting for their rights,” Stacy Stumbo remarked. “He was governor in 1959, so he was well aware of the situation. He, of course, didn’t apologize for the oversight or the trouble. And why would he? In 1960, the state won.”

|