CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

Governor of Oregon to

U.S. President: Drop dead

IF THERE WERE a category in the Guinness Book of World Records for the state with the crankiest former governor, Oregon would surely hold the title. The state would have earned the record in 1886, when it elected Sylvester Pennoyer. And Pennoyer would have clinched it seven years later with a telegram he shot off to the President of the United States of America telling him, in essence, to mind his own damn business. His precise words:

This famous telegram was in response to a note from the president, Grover Cleveland, urging western governors to take steps to make sure no Chinese people got hurt in riots or demonstrations following the renewal of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The president had sent the same telegram to the governors of Idaho and California and gotten very different replies. (Washington wasn’t a state yet.) But then, Pennoyer was no friend of the Chinese. Or any other ethnic minority either, for that matter. In fact, he owed his governorship to an incident in 1886 in which he and a mob of workers crashed an outdoor meeting being held by the mayor of Portland and turned it into a slogan-chanting anti-Chinese rally-cum-riot. His role in the riot catapulted him to the head of the anti-Chinese worker movement in Oregon, which clinched the election for him a few months later. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. Let’s take this story from the top — it’s more interesting that way.

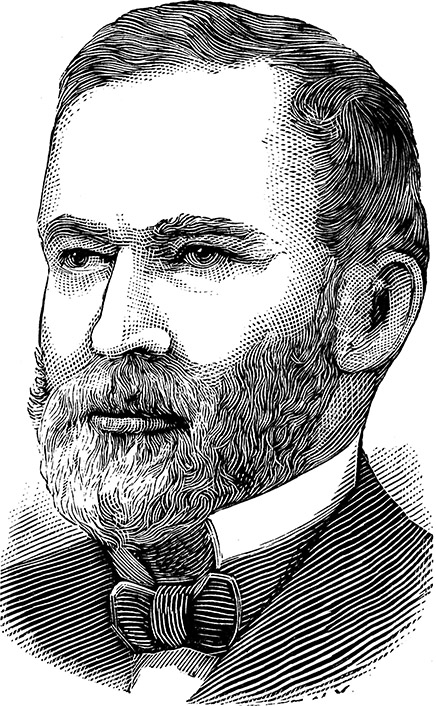

SYLVESTER PENNOYER WAS born into a prosperous family in New York, and was a graduate of Harvard Law School. He came to Portland fresh out of Harvard in 1855, and took a job as a teacher in the city’s new public school. Thereby surely hangs a tale. New graduates of Harvard, then as now, kind of had the world at their feet. There must have been some very compelling reason for Pennoyer to, rather than joining some prestigious firm in New Jersey or Boston and starting a lucrative career in law or politics, step aboard a ship for a nine-month voyage “around the horn” to the far side of the continent, where a teacher’s desk in an underfunded frontier schoolhouse awaited him. Portland in 1855 was pretty much as far away from civilization as you could get without having to live in a log hut and shoot wild animals for your supper. Whatever scandal was responsible for this career choice, Pennoyer managed to keep it quiet enough that I haven’t been able to learn what it was. But, I’m pretty sure it was there. And from what we know of the man from later in his life, it was probably a doozie! Reading between the lines, it looks most likely that Pennoyer was a classic “remittance man,” banished by his wealthy family after somehow embarrassing them and maintained in exile with regular “remittances” that amounted to bribes paid in exchange for staying far away. Even very early after arriving in Portland Pennoyer never seemed to be hard-up for money. He wasn’t a schoolteacher for long, either. He soon was appointed superintendent, and then in 1862 he quit his job and went into the lumber business, which, along with practicing law, would be his main racket for the rest of his life. At one point he acquired the Daily Oregon Herald, a short-lived Democratic competitor to the always Republican Portland Morning Oregonian; but a newsman’s life was apparently not to Pennoyer’s taste, as he sold out a year later and went back to lumbering. By the mid-1800s, Pennoyer was a prominent Portland citizen and a civic leader, active in the Democratic party. He was an unreconstructed Southern Democrat who believed the abolition of slavery to have been a terrible mistake. He was also known as a somewhat unlovable character — aristocratic and prickly, always stiffly dressed in swallowtail coats and top hats. Incongrously, though, he was a strong advocate for workers’ rights — so long as those workers were of northern-European descent. And that “man of the working people” wheeze turned out to be his ticket to the governor’s mansion. In 1886, after that rally-riot in Portland that I mentioned, he became the de facto leader of a loose movement of disgruntled white working men advocating for kicking all the Chinese out of Portland. One thing led to another, and before many months had gone by Pennoyer was running for governor, under the campaign slogan “Keep the Mongolians Out.” And, of course, he won. Twice, actually; he became the first Oregon governor to serve two full terms. He remained committed to workers’ rights throughout that time — well, white workers’ rights at least. Shortly after he took office, Oregon became the first state in the union to declare Labor Day a holiday. Railroad moguls hated him, and he returned the favor with great cordiality; he actually got the Legislature to establish a state railroad commission to regulate them in 1887. He also refused to call out the state militia after railroad workers in Albany formed an angry mob in response to their employers’ refusal to pay them. If they got their paychecks and rioted anyway, he told the railroad managers, he’d call out the militia — but otherwise, he’d let nature take its course.

WHAT PENNOYER WAS most famous for, though, was snubbing U.S. Presidents. There was, of course, the telegram thing, but that was hardly an isolated incident. A year or two before that, he’d refused to leave Salem to welcome Cleveland’s predecessor, President Benjamin Harrison, at the border when the nation’s leader arrived in Oregon on a railroad tour in 1891. “I have no business to go to pay homage to him,” Pennoyer told a newspaper reporter at the time. “On the contrary, when he visits Oregon, he should rather pay his respects to me.” Pennoyer subsequently relented and agreed to leave the capitol building to meet Harrison at the Salem train depot, where he kept the commander-in-chief and a large crowd of onlookers waiting in the rain and arrived 10 minutes late.

|

When Cleveland was nominated, Pennoyer was so upset that he bolted the Democratic Party and joined the Populist Party, becoming the second Populist Party governor in history (and the only Populist Oregon governor). And when Cleveland won the election, Pennoyer refused to let the Oregon Democratic Party use the official state cannon to fire a salute in celebration. “No permission will be given to use state cannon for firing a salute over the inauguration of a Wall Street plutocrat as president of the United States,” he said, and locked the thing up under armed guard. The Democrats won this standoff by their wits: They forged a court order commanding the sheriff to confiscate the cannon as collateral for the payment of an imaginary unpaid bill for blacksmith work — then got it from him and fired the salute. One imagines they likely took special care to fire it within earshot of the governor’s office — but on that point, the record is silent.

A FEW MONTHS later came the Thanksgiving debacle, in which Pennoyer essentially arranged for Oregon to have two Thanksgivings. The double-turkey-day story has already been told in an Offbeat Oregon column (which you’ll find here) but in a nutshell, Pennoyer made a point of issuing his yearly Thanksgiving proclamation early, so as to beat President Cleveland to the punch. Unfortunately, when he did, he named the wrong day. He proclaimed the fourth Thursday of November as Thanksgiving; however, at the time Thanksgiving was always held on the last Thursday of the month. Most months only had four Thursdays in them, so it came to the same thing; but 1893 was not one of those years. Rather than admit his mistake, Pennoyer doubled down and announced that Oregon would celebrate Thanksgiving on the day he said. Accordingly, in 1893 and again in 1894, state offices and agencies all closed down on Pennoyer’s Thanksgiving, and were open for business on the real Thanksgiving that year. This must have messed up some state workers’ holiday plans. The following year, there were once again only four Thursdays in November, and Pennoyer’s calendar once again called for Thanksgiving on the same date as the rest of the nation. By the time another five-Thursday month of November came around, Pennoyer was safely out of office, and nothing further was heard about Oregon’s second Thanksgiving.

DURING HIS TIME in office, Pennoyer’s cantankerousness earned him the nickname “Sylpester Annoyer” from pioneer judge Matthew Deady, and the Portland Morning Oregonian took to referring to him in editorials as “His Eccentricity.” For a time there was talk about running him on a Presidential ticket, but such talk died instantly, of course, after he bolted the Democratic Party. Among voters, though, Pennoyer was still hugely popular. After his two terms as governor, he went on to become mayor of Portland. There, in an ironic twist, he presided over the dedication of the city’s new water system sourced from the Bull Run River — which has, ever since, enjoyed a nationwide reputation for purity. As governor, Pennoyer had vetoed the legislation that gave the city of Portland authority to sell bonds to raise the money for Bull Run. Portlanders were furious; before Bull Run, the city’s water came from the Willamette River, which, by the time it arrived in Portland, carried with it the toilet-flushings of Salem and Eugene as well as several dozen other upstream towns. It was making people sick; and here was the governor — who, being as he lived in Salem, was one of those upstream flushers — trying to block them from doing something about it. His justification for the veto was ridiculous enough that many suspected he was just being deliberately obstinate. It would, he claimed, “cause goiter in the fair sex of Portland” because it originated in glacier water. Luckily, the city had other financial resources, and it called upon them and got the project built ... just in time for its greatest opponent to preside over the dedication as Mayor of Portland. Yes, Pennoyer had, in the time it took to overcome the obstacles his veto imposed on the project, stepped down as governor and been elected mayor. At the ceremony, Pennoyer was given the first cup of water from the new system so that he might take the first sip from it. This he did, and then, putting the cup down, he declaimed, “No flavor. No body. Give me the old Willamette.”

PENNOYER SET THE tone — in ways both good and bad — for politics in Oregon for decades. In the early 1900s, Oregon would become known as a land of people like Pennoyer — crotchety mavericks, proudly libertarian and frankly populist, friendly to workers so long as they were of northern-European descent, with a sometimes slippery interpretation of the rule of law. You’ll still hear echoes of that spirit in Salem to this day.

|