CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

Femme fatale’s murder plot was like real film noir

Their letters got more and more torrid. She told him she was a war widow, her husband (Leslie) having been killed in London during an air raid. She also told him she was in the process of inheriting $3 million from an aunt, to allay any suspicion that she was gold-digging. And to guard against the possibility of Leslie getting wise and spilling the beans, she told Dr. Broady that she was being stalked by Leslie’s evil twin, Lester, who was impersonating his dead brother and trying to force himself upon her with an eye toward grabbing her inheritance. Which was pretty clever, you have to admit. And between that, and the fact that the woman dishing up this whopper was someone he considered to be not only the hottest woman he’d ever dated, but one of his oldest friends — we can’t be too hard on him for lapping it right up. Which, of course, he did. A couple months later, in a letter, she suggested the two of them ought to get married. So, on May 20, 1946, the two of them met up in Reno, pulled a marriage license, and the following day were (bigamously) married.

MONTHS WENT BY. Gladys and Dr. Broady kept their marriage a secret, ostensibly to avoid trouble with the evil twin brother, but really to give Gladys time to get divorced from Leslie. But a few months after the marriage, Leslie intercepted one of Broady’s letters, along with one from his sister, and that escalated things a bit. Gladys didn’t drive, so she had to come up with a story that would bring Dr. Broady on the run to rescue her. So she came up with a story about having blood poisoning in her foot, and a potential looming amputation. Dr. B, of course, came on the run, and picked her up and brought her home in his fancy cream-colored 1941 Chevrolet Deluxe coupe. That was great — among other things, Dr. Broady was able to get her into the hospital to get her barbiturate addiction treated. He seems to have accepted that the drugs were the source of the blood-poisoning story, as there is no further reference to it. But a few weeks later the sheriff tried to serve papers on her, and she realized that those papers probably were divorce proceedings. What would happen when her second husband realized she was still married to her first, and had lied about the evil twin brother? Nothing good. She knew she had to act. So she told Dr. Broady she needed to go back to Sacramento and take care of some business connected with her pending inheritance. It was harvest season, so he couldn’t go along; instead, he paid a young ranch hand $5 a day plus expenses to go along with her to California and do the driving. That young ranch hand, just 23 years old, was named Alvin Williams. And a week or so later, there he was — watching “The Postman Always Rings Twice” with the hottest woman he’d ever dated, who had initiated a torrid adulterous affair with him on the second night of their road trip.

Then she and Alvin returned to Dr. Broady’s ranch in Jordan Valley. A few days later, Dr. Broady was getting ready to go out for his annual elk hunting trip. Gladys told him she was very nervous. He would be out of pocket for days, riding on the range. What if something should happen to him, she asked? Her $3 million inheritance was still in probate. She wouldn’t even have enough ready money to cover funeral expenses! She told him she was dreadfully worried about him, almost frantic, and worried that if he got killed out on the range she would be left hanging in the wind. So the unsuspecting Dr. Broady went to his attorney’s office and had a new will drafted and approved, leaving his entire estate to her. There, he said, don’t you feel better now? And he continued with his preparations for the hunting trip. Meanwhile, Gladys and Alvin were spending a lot of time together. They discussed various ways of putting Dr. Broady out of the way. She had brought him fully on board with her “Postman Always Rings Twice” plan by telling him vivid stories of Dr. Broady’s cruelty, and the poor lovestruck young dolt does not seem to have ever questioned it. They decided he would ambush Dr. Broady on the highway north of Jordan Valley, as he was driving to the ranch with his pinto horse in a trailer behind. She gave Alvin $200 to buy an old Ford Model A to use to do it, since everyone knew Dr. Broady’s Chevrolet. Alvin, equipped with his bedroll, a single-barrel Stevens 12-gauge shotgun, and half a gallon of whiskey, drove out to the intersection of the I.O.N. (Idaho-Oregon-Nevada) Highway and Succor Creek Road, pulled over, and opened the hood. The plan was to get Dr. Broady to stop and try to help fix the car. Then when he was leaning over the engine, Alvin would crack his canister as hard as he could with a big crescent wrench that he’d picked out of the tool box. If that didn’t work, a dose of bird shot from a few feet away would finish the doctor off. Then he’d drag the corpse into the brush and hide it, get rid of the shotgun, and hide the Model A someplace until the coast was clear. And, well, that’s basically how the crime went down. But because nobody involved in this operation was very smart, the conspirators didn’t take some important things into account. The first was that in Jordan Valley, then as now, if you’re pulled off the road with your hood up everyone who drives by is going to stop and try to help you. And yeah, there isn’t much traffic out there; but if you’re sitting there all morning and afternoon, someone will drive by, and stop, and ask if you need help. That someone will think it’s weird when you say no, your buddy has gone into town for some car parts and will be right back, but you’re still there four hours later when he drives back through. And, of course, he will remember you and your car in some detail when he learns someone got murdered at that very location a few hours later. The second is that if you’re 23 and sleeping with the boss’s wife, everybody knows. You might think you’re being real discreet, but you’re 23; you wouldn’t know discreet if it got drunk and punched you in the nose. Everybody on the ranch knows what you’re doing, and when the boss turns up murdered, it will occur to them that statistically, people who don’t take the Seventh Commandment very seriously are less likely to be sticklers for the Sixth than folks who do. And the third is, when a man’s horse shows up at his house without him, everyone goes straight into search-and-rescue mode. Which, of course, they did. And they found Dr. Broady’s pickup and horse trailer later that night, and the Good Samaritans who stopped and talked to Alvin remembered him, and told the sheriff, and ... There is an interesting moment in the newspaper coverage of this crime, which appears to capture the precise moment when Gladys realized her goose was cooked:

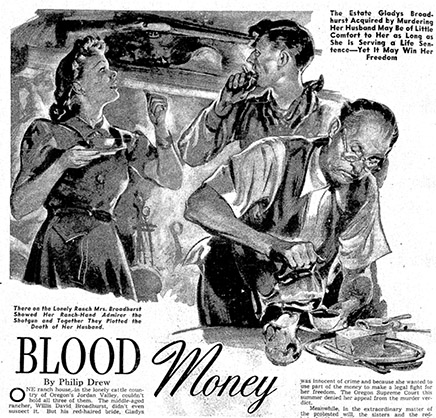

|

Then Alvin broke down and confessed the whole thing, and led police to the wash where he’d hidden the body and the shotgun.

Including, interestingly enough, her very presence in the courtroom during her trial: “For two long weeks, you have observed her charm and her magnetism,” District Attorney Charles Swan told the jury. “I think it has made itself felt on every person she has met. If you can see and feel the impact of such a person in a proceeding such as this, I ask you to imagine, if you can, the effect on a youth who lived with her for many weeks.” Alvin, Swan said, fell under the spell of that magnetism, and became her “obedient slave.” “Without Gladys Broadhurst,” Swan added grimly, “there would have been no murder.” Not so, riposted Gladys’s attorney, Patrick Gallagher (the grandfather of her biographer). He told the jury that yes, his client was a double bigamist, a morally bankrupt habitual drug abuser and steeped in carnal sin; but that didn’t make her a murderess. “Gallagher argued that the love affair (with Alvin) had blown up, and that Williams ‘was on his way out’ when he murdered the doctor ‘to get back to her again,’ ” reporter Moxley wrote in one of his Oregonian stories. The jury didn’t buy it. She was found guilty of first-degree murder, and sentenced to life in prison. The sentence was controversial; most Oregonians really wanted her to swing for the job. “Some of our brethren of the press are complaining about Mrs. Broadhurst escaping the death sentence and are blaming it on the jury which convicted her,” wrote the editor of the Corvallis Gazette-Times in a March 17, 1947, editorial. “Perhaps the jury was convinced by the same thing that got for Mrs. Broadhurst her seven husbands.” It does seem likely. But her lenient sentence probably saved Alvin’s life, because, as the judge pointedly said, it would offend justice to have him punished more severely than the person who set him in motion to do her will. In any case, Alvin drew the same sentence — life in prison — but his conviction was for second-degree murder, not first-.

Alvin married a woman named Nina Cantrell two years after his release, and settled into family life, raising a family with her in Idaho. He died in 2010. As for Gladys, she apparently kept her nose clean for the requisite several years after her release. But she also reached out to an old flame from the Sacramento days, a man named Leo O’Shea, more or less following the same playbook that brought her back to Dr. Broadhurst; and in May of 1961 — probably because that was the end of Gladys’s term of parole, which would have been five years — O’Shea came to Salem and the two of them got married. She moved with him to Sacramento, and apparently lived in contentment with him until her death in 1973. And they must have gotten along pretty well, because after she died he laid her to rest in the family cemetery plot and had a grave marker made that read, “GLADYS O’SHEA, 1906—1973 / JOHN O’SHEA, 1903—,” with a space for his own date of death to be carved in, when the time came.

Or Cora Smith, Lana Turner’s character from “The Postman Always Rings Twice.” It’s still weird to contemplate her there in the theater, watching that movie and interpreting it not as a horrible warning, but as a shining example of how to get her paws on her new husband’s money. In the movie, of course, Cora comes to a bad end, dying in a car crash; and Frank, the drifter she vamps into murdering her husband, is sent to the gas chamber for killing her. In classic films noir, the kind that were popular in 1946, the femme fatale always does. Often she’s killed. Sometimes she’s sent to the gas chamber. But never, in a classic film noir, does the murderess actually win. She does not inherit $800,000 from the man she vamped and murdered, serve a brief term in lady-jail, move to another state, and start a new life with her eighth husband as a respectable society lady, dying of old age many years later at the end of a long and contented life. Gladys did, though. Dr. Broady’s sisters contested the will that she conned him into making a week before she had him killed, and despite state law being very clear that she wasn’t entitled to collect, the sisters cut a deal with her — probably just to get her out of their lives. They gave her roughly one-third of the estate — clear title to the Jordan Valley ranch. It was sold for $51,000, which was the equivalent of just over $800,000 today. Of course, her legal bills ate up a lot of this. A few years after her trail ended, her attorneys built a new office building in Ontario, and local residents took to calling it “The Broadhurst Building.” But there has to have been some left over. It’s not clear what she did with it. Maybe she purchased a new husband with it! And, about that husband. He seems to have been happy with her as a wife; but when he finally died, in 1985, he was not buried with her in the family plot. The space on the gravestone for his date of death was left blank, and the grave left unfilled. Instead, the family purchased a new plot, in a cemetery a mile or two away, and laid their loved one to rest in it alone ... where they could lay flowers on his grave and not hers.

|