CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

Heroic skipper refused to risk passengers for ship

But he could see his gamble in making full speed for shore was going to pay off. The Telephone was going to make it in time. Nobody was checking, of course, but it’s a safe bet that the Telephone was moving faster than it ever had before (or would again). In a few moments it would be connecting with the riverbank at probably 25 miles an hour. The passengers packed into the bow braced for impact as best they could. Then the Telephone fetched up on the Oregon side of the river. Luckily, the shore there was basically a mud flat, which buffered the impact. Still the Telephone dealt the state of Oregon a mighty blow, and passengers went flying to the rapidly-heating-up foredeck. There probably were some injuries; the record doesn’t say. Whatever those injuries might have been, they weren’t enough to keep a single passenger on that by-now-dangerously-hot deck once the boat hit the shore. Over the gunwales they went, splashing into the water and mud and clambering up on shore to watch the Telephone burn.

AFTER WATCHING THE last of the passengers disembark, Scott turned to leave, but found to his consternation that the fire was surrounding the pilothouse and had burned away the steps. So he opened the pilothouse window and bailed out. Most sources say he executed a swan dive, but this seems unlikely given that the Telephone was stuck in mud and the pilothouse was pretty close to the front of the ship. More likely, it was something on the order of a belly flop or cannonball. The Telephone burned to the waterline as the passengers watched and firefighters from Astoria did what they could. When all was done, they found one single body in the wreckage — that of an unfortunate fellow who had just picked a really bad time to get drunk, and had either passed out or been too befuddled to find his way upstairs. Everyone else made it.

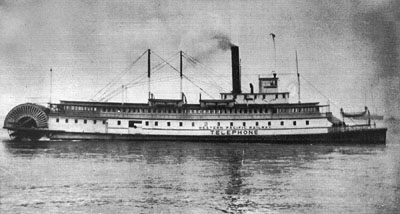

AFTER THIS DISASTER, the competing Oregon Railway & Navigation Co. reached out to Captain Scott with an offer that, in retrospect, seems irregular if not outright insulting. They offered to reimburse him for the loss of the Telephone if he would agree to go to work for them; they’d have him rebuild their riverboat Wide West and take command of her. Otherwise, they said, they’d take advantage of his misfortune to run him off the river. Scott told them if they’d throw in an extra $120,000, he’d consider it. That was too much for them, though, so no deal was struck. The Telephone was rebuilt — some sources say the hull was salvaged and a new superstructure put to it, but historian Jerry Canavit reports the new Telephone was a complete new build, slightly larger than the old one. Most likely this is the case, as the new Telephone, although still the fastest thing on the river, was never as fast as the old one. But then, she never had to be. Scott continued running the Telephone between Portland and Astoria till 1903, when he sold her to the Arrow Transportation Co. She enjoyed a reputation for blinding speed the whole time, right up until the end, and finished her days as a ferry on San Francisco Bay. She was finally scrapped in 1918.

|